John bends down near the edge of the ball pit, as though tying his shoe, and with a flick of his wrist deposits thousands of hungry ticks. Each time it’s the same. I go first and wait in a booth, sipping a coffee. A few minutes later he enters the restaurant, and drops his payload among the other balls. His little ritual of ecoterror is over in seconds -- it’s hard to catch, even knowing to look out for it. At the third McDonald’s I manage to spot him palming a ball from his pocket. But I immediately lose track of the ball once it lands in the pit.

“Bug bombs, I call them,” he tells me when we’re back in the car, a rented silver Toyota he’d been driving since he picked me up in Iowa City. We’re between the third and fourth McDonald’s, heading toward Chicago. The route feels random. But I think it’s just John covering his tracks -- just like his plastic balls, which he says he sourced from the same manufacturer that McDonald’s uses.

"Of course, properly speaking," he says, "ticks aren’t true bugs at all. No serious natural scientist would confuse the two."

“And do you think of yourself as a scientist?” I ask. “Is this an experiment?” The skepticism I had before this trip has vanished, replaced by a sweaty feeling that I should’ve called the police, probably right after he showed me his cooler. But I have no idea what I would say even if I did. Hello, officer? I’m a reporter for the Times and my source is a madman who’s been infesting America with ticks.

“Look,” he says, “I was this goddamned close to my Ph.D.” -- he takes a hand off the steering wheel to hold up his thumb and forefinger a centimeter apart -- “when Princeton kicked me out. Is that good enough for you?” (I’m fairly certain John Chapman, aka Appleseed, is his idea of a joke. Yesterday I phoned Princeton’s graduate department, just to be sure, and they have no record of a student named John or Jonathan Chapman.)

The edge in his voice makes me nervous so I say I’m curious how he gets the ticks to crawl into plastic balls.

It was easy, he says. He just drills a tiny hole in the bottom and then fills the ball using a funnel.

“You can get ticks to go down a funnel?” I imagine a swarm of ticks marching in line, like ants.

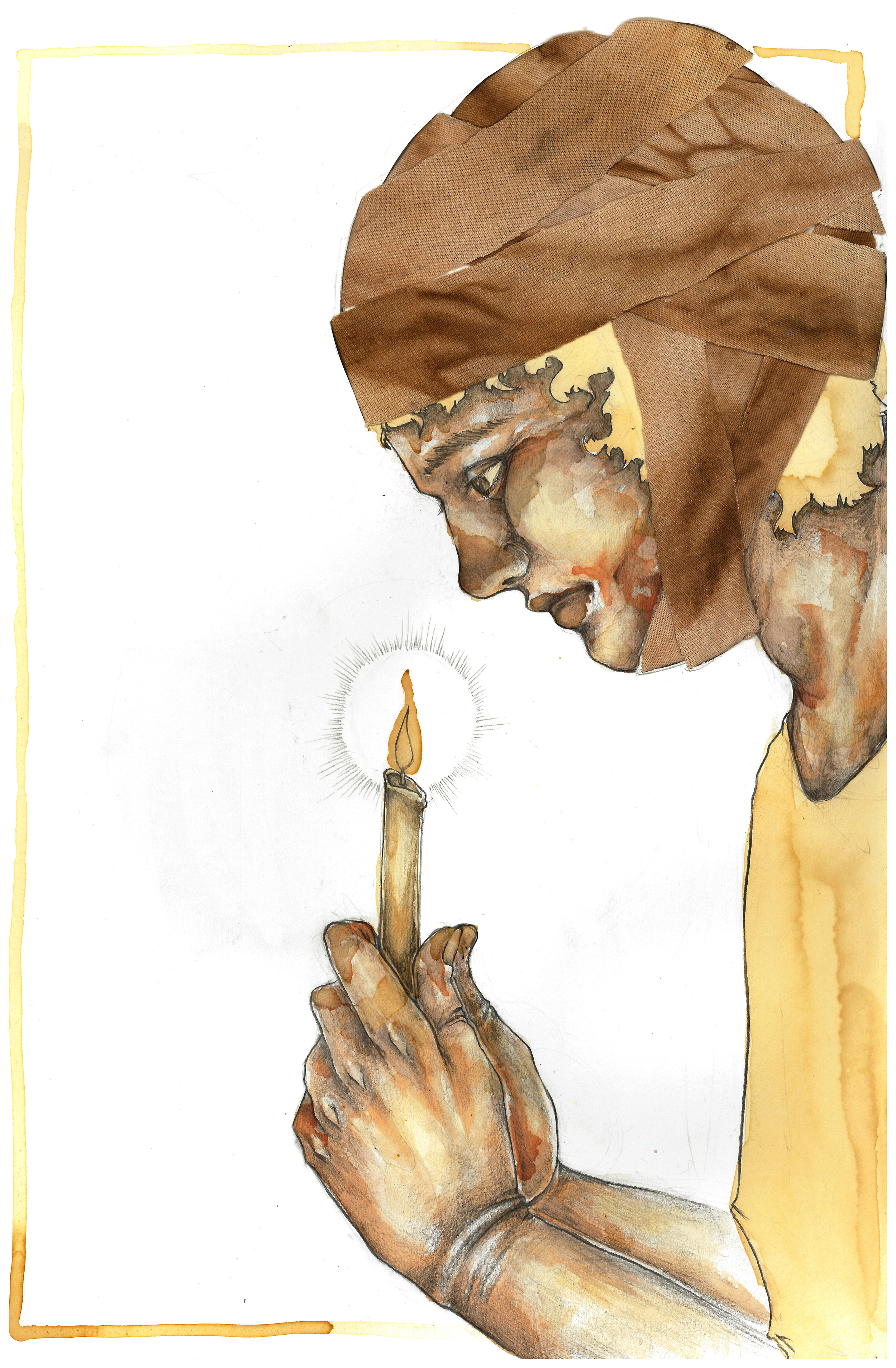

“I can if they’re nymphs. Immediately after my larvae molt into nymphs, I chill them,” he says. “It doesn't hurt. It happens like this in the wild, too, in winter. If they get cold they start to hibernate, and when they’re sluggish they pour as easily as sugar. Plus, once they wake up, they have an incredibly accelerated metabolism. They’re rapacious. They’ll bite anything as long as it’s warm and has a pulse.”

“In a way,” he adds, “they’re really the perfect animal for what I’m doing. A gift from nature.”

If I'm going to quote him I should be writing this down in my notebook, but instead I’m fighting the urge to bring up the sick kids. It’s not the right moment, mostly because I’m not prepared for what he’ll say. Or what he’ll decide to do as we speed down the interstate. So we don’t speak until we pull into the next McDonald’s.

John reaches back into the cooler -- he’s brought along one of those large red ones, the kind you’d find filled with Bud Lights and Coronas at a family reunion -- and begins rummaging. He has a system: the Coke cans he’ll surreptitiously litter in parks and playgrounds; the hollowed-out ashtrays are for the bars and steakhouses that still let you smoke; the 35-mm film canisters he dumps pretty much everywhere else, in dressing room corners at The Gap or under movie theater seats or behind the toilets at baseball stadiums. He says those little black cylinders house enough nymphs to trigger allergies in a hundred people.

But it’s the ball pit balls, I can tell, that are his favorites. “Billions and billions served,” he says as he paws through the cooler until he finds a ball. He peels off a strip of scotch tape to expose a small hole.

“I think I’ll sit this one out,” I say.

John shrugs, tucks the ball into his jacket. “Are you hungry?” he asks. “Maybe a burger?” It’s his way of being funny.

I flip through my notes while John sabotages the fast food restaurant. There's a copy of his cryptic emails, the ones in which he annotates all the errors he saw in my first article. Next to a rash of mysterious meat allergies, he’s written “galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose.” That was meaningless until I looked it up. It’s a chemical, a carbohydrate sugar, embedded in the cell membranes of most mammals. Thanks to an ancient evolutionary quirk, humans don’t have it. We can digest it, but if something -- a specific type of tick, say -- bites us that's bitten another mammal, it passes this sugar into our veins. Our immune systems go haywire: hives, nausea, the whole bit. I pull up a recent Reuters report on my phone. Three kids in Nebraska went into anaphylactic shock after snacking on 7-Eleven hot dogs. As with the other cases, the FDA has ruled out food poisoning. Signs of an allergic response, it says.

When the car door opens I almost bolt. I didn’t hear him coming. John sees me and then my notebook. He makes a face. “You want to ask me about those kids,” he says as he buckles himself in. “I’m sorry about them. Really. But take my view from thirty thousand feet up-- more people are going get hurt, going to die if I don’t do this.”

Instead of what I really want to say, which is to call him a lunatic, I ask him how he figures.

“Global warming will be the biggest holocaust humanity has ever known. Cities will drown and economies will collapse. And the worst part is that it’s driven by our bullshit,” he says. “Not literally shit, but flatulence. Red meat is killing the earth, one burp of cattle methane at a time. Did you know there are a hundred million cows in our country? Each spewing out three hundred pounds of methane a year. If every American stopped eating beef, it would do more for the planet than if we all stopped driving.”

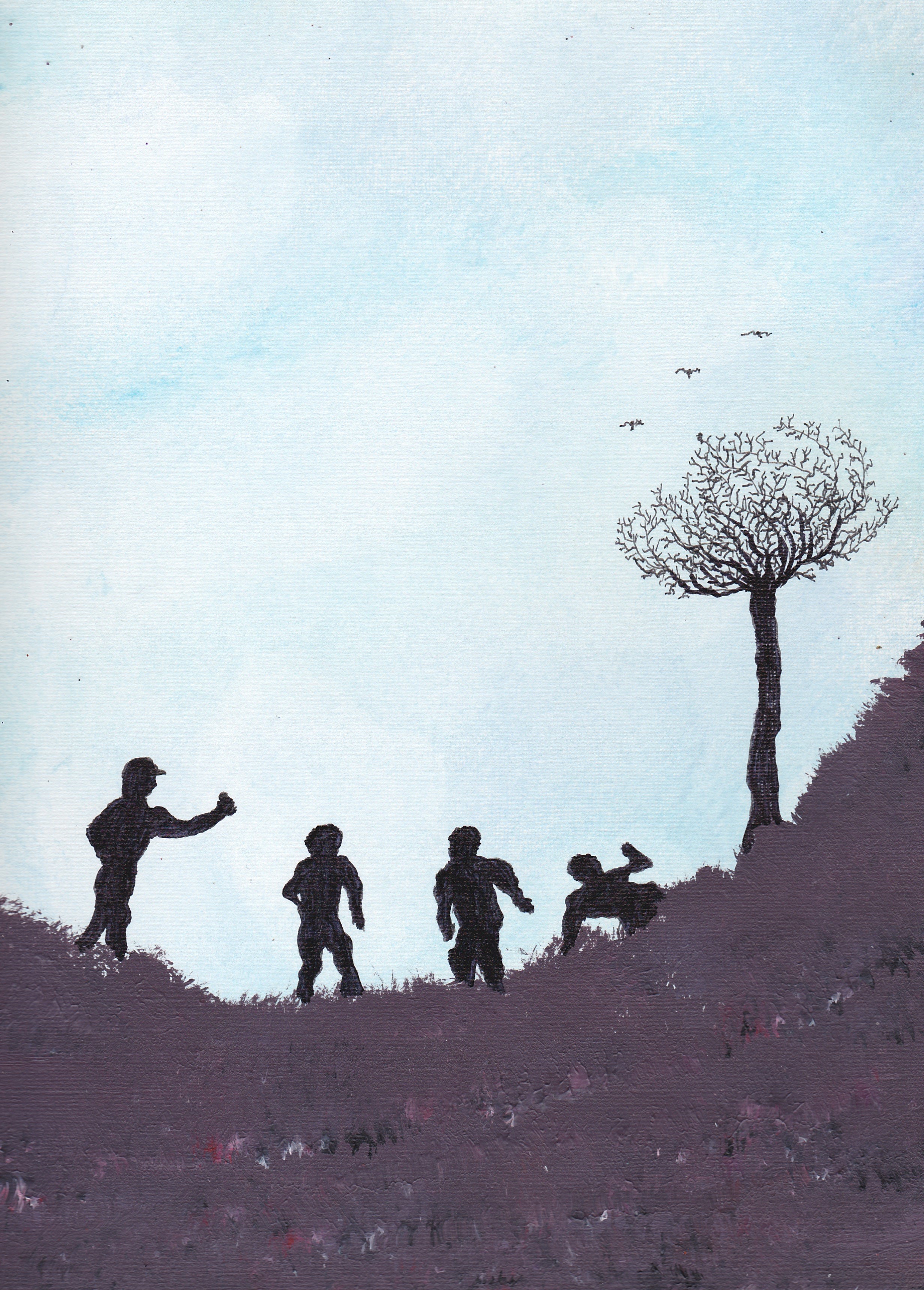

“Do you really think your bug bombs will make every American allergic to Big Macs?”

“Not every American, no. But are you familiar with the economic idea of a tipping point? If we get through to a fifth of the population, everyone else falls in line.”

“I’m not sure that applies to infecting people at random.”

“They’re not infected. Most people who get bit will eat a hamburger, get a rash, and then have to get used to eating chicken.”

“Someone could die.”

“It’s possible. But we’re all indirectly killing each other. That's life. Do you think my former colleagues aren’t? Those assholes jet to conferences around the globe to set emissions standards, which won’t work, and pat each other on the back. They might as well be shoveling the Marshall Islands into the Pacific themselves. For Christ’s sake, airplanes are the least efficient form of travel we’ve ever invented.”

He pulls off the highway, down a road lined with cornstalks.

“You know, I asked you to come meet me -- to see this work -- because I like your stuff. It’s good,” John says. “You care, like I do.”

“I’m not like you.”

“Maybe, maybe not. But there isn’t a better way to save the planet,” he says. “Now get out of the car.”

He hasn’t let me totally alone. There’s a dairy barn across the street. I wonder if this was part of his plan all along, or just farm country providence. I catch the dull eyes of the cows, smell their bovine farts baking the heat of the sun. I dial a cab instead of the cops.

I’m hunting for an aspirin later at my hotel when I spot them crawling out of my backpack.

Ben Guarino is a science journalist and staff writer for The Washington Post. His nonfiction work has appeared in the Huffington Post, Salon, Inverse and others.